Annie McClanahan wrote:

Because the state is so incredibly powerful, any student debt mass

default/debt strike movement would have to set up really powerful

structures for mutual aid. That's why I find the Student Debtor's Pledge

(http://www.occupystudentdebtcampaign.org/student-pledge/) in which

signers pledge to default once 1 million others have similarly promised

a much more powerful organizing model than the Rolling Jubilee (which

uses a philanthropic system to collectively buy back non-secured loans,

anonymously, but in no way threatens the debt system as a whole

I agree with the above, signed the plege almost a year ago (as adjunct

faculty) and began researching about student debt, writing about it and

talking about it publicly whenever possible. However, the sobering thing

is that to date, only some 4,500 debtors have signed that pledge, and

only some 600 faculty. Like Annie, I doubt the moral argument is the

decisive one that stops people from taking action. The stronger forces

appear to be fear of the legal system and simple apathy, or the sense

that one has no agency whatsoever to effect change. Perhaps a third

force is self-interest, since the expansion of the university system

from the 1970s up to 2008 was predicated (without anybody ever talking

about it) on each university's capacity to draw in the revenue stream of

student debt. And it's still going on.

How can crippling debt become an issue on campus, given that the

students have yet to be affected by it, while the faculty are actually

paid with student debt? How to break the status quo of isolation and

corruption? What can we do to transform the basis of social solidarity

that Annie talks about in her post?

One of the things that always interested me was how the rebellious

students of the 1960s were reintegrated to the capitalist system after a

decade of deep disaffection. In the late 1990s, the rhetorical

mechanisms of this reintegration were demonstrated in books like "The

Conquest of Cool" by Thomas Frank or (with a more extensive sociological

apparatus) "The New Spirit of Capitalism" by Boltanski and Chiapello.

The basic idea was that changes in marketing and management styles had

put to rest the alienation experienced by young cadres in the 1960s and

70s, to the point where we were living in a new kind of networked dream

world (a new ideology). Demonstrating this in detail seemed like a

breakthrough at the time. Yet the magnitude of the current problem makes

that work appear totally inadequate.

In fact the crisis of the 1970s, and the threat it posed to capitalism

as a whole, was overcome through a tremendous expansion of middle-class

status, representing not merely an ideological but also an economic

cooptation of those who were needed to manage the major social

transformations that we call globalization. From the 70s onwards the

core functions of governance became Trilateral (US-Western Europe-Japan)

and a transnational capitalist class gradually emerged (as described by

Leslie Sklair or William Robinson). The 1990s and especially the 2000s

were marked by the urban phenomenon of megagentrification, or the

construction of giant new metropolitan centers to serve this new class,

whether in Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America, or in the older core

regions. Today, the Trilateral envelope has been ruptured. State,

financial, corporate and millitary actors now have to contend with

sovereign forces across the entire planet. Members of the global middle

classes (that's us) use computer networks to contact peers across the

world, to organize business, pleasure, or occasionally, revolt. But how

did this occur? How did we get here?

Right now I'm reading "The New Depression" by Richard Duncan, who gives

a surprising answer (you can also read a long interview with him, posted

for free at newleftreview.org). According to Duncan, we got here by

shifting from capitalism to creditism. In 1968, Johnson revoked the law

requiring the US to back its currency with 25% reserves in gold. The

Bretton-Woods system then collapsed in 1971, and not only did the

world's currencies begin to float against each other, but also the US

began issuing increasing amounts of paper and electronic dollars.

Meanwhile we began importing far more than we exported. Corporations in

the producer countries, especially Japan and later China, ended up with

the excess dollars. The governments of those countries then printed more

of their own money, bought up the dollars, and invested them in US bonds

(including huge amounts of government-backed housing bonds). All this

sovereign money creation served as the basis for the issuance by private

banks of much larger amounts of credit -- and the capitalist system

expanded wildly on the basis of what Marx would have called "fictitious

capital."

The point, however, is that the fiction was effective. The endless

factories and entirely new cities that now cover the coastline of China

are there to prove it -- and on a smaller scale, you might also have a

look at the shiny new physical plant and complex corporate and

international partnerships of all the more successful universities. The

global middle classes were created and integrated to the neoliberal

version of capitalism by means of a credit bubble that has expanded

continuously since the 1970s.

Since 2007, the Federal Reserve has isued many trillions more dollars

worth of this imaginary but effective money, most recently via the QE3

program that is designed to pump out $40 billion *per month* for an

indefinite period. This is being used to go on bailing out the banks and

sovereign investors by purchasing toxic assets, especially those based

on mortgages, which account for some 40% of total US debt. The immediate

effect of quantitative easing is to reflate stock and commodity prices

(incidentally sending food prices through the roof). Over the middle

term, the aim appears to be to bring everything back to the status quo

ante. The current economic model - from wage stagnation and predatory

lending to global just-in-time production and devastating climate change

- is being propped up by the Fed with help from the EU, Japan and China.

It is as though they believed a new expansion of capitalism were

possible, that all the currently disaffected people could be brought

back into the system once again, and that we could end up with a fully

integrated global governance: the scenario of the 1980s and 90s,

reloaded at a higher power.

The other, undiscussed but in my view far more likely scenario, is one

of major breakdowns in international economic relations, resulting in

conflicts exacerbated by climate change. Something like a variation on

WWII, a rolling planetary civil war whose first act has been the Arab

Spring - arguably sparked by the historic rise in food prices in 2010.

How to make student debt a focus of struggle on college campuses? How to

challenge the reckless pursuit of creditism on the global scale? The

questions are linked. Because of the orders of complexity involved, only

the university can produce a counter-discourse to the neoliberal

creditism that currently governs our planetary society. But we know how

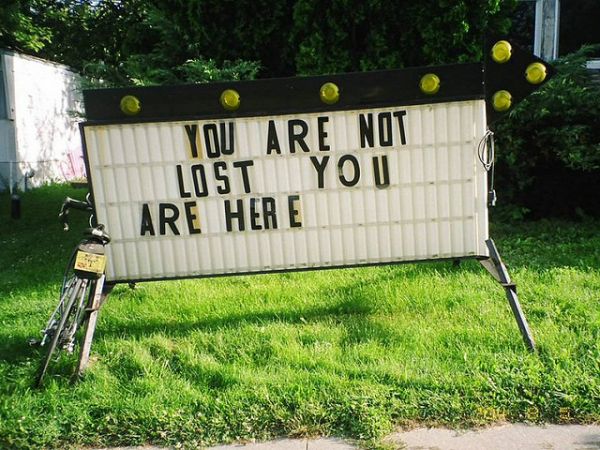

the university works: people just get lost in all that complexity. Only

a social movement of students, grads, adjuncts and (with more

difficulty) professors, acting in solidarity with the other debtors in

our societies, can give such a counter-discourse the force of acts, the

real power to refuse the status quo.

let's do it,

Brian

_______________________________________________

empyre forum

EMPYRE MAILING LIST